Microsoft this week detailed its legal efforts to seize domains related to a “sophisticated, new phishing scheme” that’s taking advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic to attack customers in 62 countries.

“Our civil case has resulted in a court order allowing Microsoft to seize control of key domains in the criminals’ infrastructure so that it can no longer be used to execute cyberattacks,” said Tom Burt, Microsoft corporate vice president for customer security and trust, in a blog posted Tuesday, the same day that the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia unsealed documents from Microsoft’s lawsuit.

The Microsoft Digital Crimes Unit first got wind of the malicious activity, which it classifies as a business e-mail compromise attack, in December, although at that time the attack’s messaging did not incorporate COVID-19 themes.

Back then, Microsoft had employed technical measures to block the attacks. Without saying so explicitly, Burt’s blog implies that criminals ramped up their effort as they realized that worldwide concerns over COVID-19 could lower individual executives’ routine wariness of suspicious messages and attachments.

“In cases where criminals suddenly and massively scale their activity and move quickly to adapt their techniques to evade Microsoft’s built-in defensive mechanisms, additional measures such as the legal action filed in this case are necessary,” Burt wrote.

Like most phishing attacks, there were several parts to this attack. The cybercriminals designed phishing e-mails to look like they originated internally. Subject lines and message body text involved pandemic-related financial concerns. A key element of this attack was malicious links, such as an apparent Office attachment with a filename like “COVID-19 Bonus.”

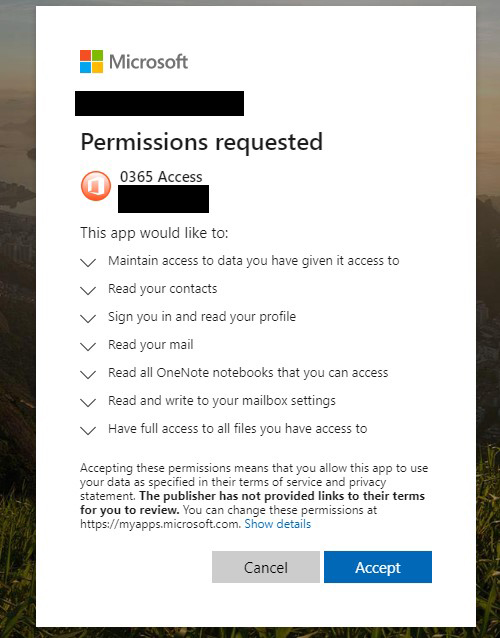

Clicking on the deceptive link led to a prompt from a malicious Web application asking the user to grant various permissions. As shown in a consent screen included in the Microsoft blog, the user could be allowing the attacker to access data, read contacts, read mail, view OneNote notebooks, send mail and get full file access.

The attack differs from simpler phishing attacks, which might send users to a sign-in screen, where they would be prompted to enter a user name and password to access the file or follow the link, and where small mistakes or inconsistencies in the interface might give users clues not to click any further.

Burt said the civil case allowed Microsoft to “proactively disable key domains that are part of the criminals’ malicious infrastructure.”

Microsoft also recommended that organizations protect themselves by enabling two-factor authentication on e-mail accounts, reviewing how to spot phishing schemes, enabling security alerts about links and files from suspicious Web sites and checking e-mail forwarding rules for suspicious activity